It’s common for words to shift in meaning in ways that tie biased assumptions to otherwise independent concepts, which is why trying to create positivist science from pure deductive language is a futile endeavor (*cough* praxeology *cough).

“Objectivity” & “subjectivity” are 2 concepts that fall victim. People oft simplify these concepts as simply meaning “unquestionably right” & “all answers are right”–to concepts which don’t e’en add up to the total o’ all possible truths regarding any questions (a question could have mo’ than 2 answers, some equal in “rightness” & some unquestionably inferior).

This is what people mean when they say that morality is “objective”: that certain answers are unquestionably right & that people who argue gainst these answers are unquestionably wrong.

In fact, what these 2 words truly mean is what a concept has in relation to reality. “Objectivity,” being based on the root object, means that something has a basis in concrete reality, whereas “subjectivity” focuses on subjects, abstract concepts that exist only in one’s mind. The true dichotomy is not “1 answer is unquestionably right” & “all answers are right,” but the dichotomy ‘tween the concrete world that exists outside human minds & the conceptual world that exists within peoples’ minds.

Now, ¿what is morality? Morality are questions o’ what should be, as opposed to questions o’ what are, which are scientific questions. For instance, the much-misunderstood theory o’ natural selection, in contrast to what creationists think, is not a moral question @ all, but simply an explanation for what is. It is perfectly consistent to believe that it’s objectively true that natural selection determined the proliferation & withering ‘way o’ varying species o’ animals & to also believe that this should not be the case. What is is not the same as what should be.

“Should” is nothing mo’ than a reflection o’ human values. Indeed, without mental consciousness, there exists no “should,” though there does exist what is. Should is merely a reaction that exists in human minds, in abstract–it is purely subjective.

This distinction ‘tween “what is” & “what should be” is important, since it provides a rebuke gainst the trite argument that belief in moral subjectivity is inherently contradictory, since it is an objective statement. The lack o’ existence in any objective (or e’en “unquestionably right,” as I will note later) morality is not itself a moral statement, but a simple statement o’ what is real. (This point has an interesting ethical consequence that does, however, hurt some o’ the arguments that the mo’ vulgar acknowledgers o’ subjective morality, which I will write ’bout later in this post.)

The closest one could come to existing an objective element to morality is merely the question o’ whether what “should be” is physically possible. But that’s a small (& in almost all serious moral controversies irrelevant) limitation. For instance, one could not prove that Hitler or Nazism are objectively wrong in this case, since it’s an unquestionable fact that they existed, & thus are consistent with objective reality.

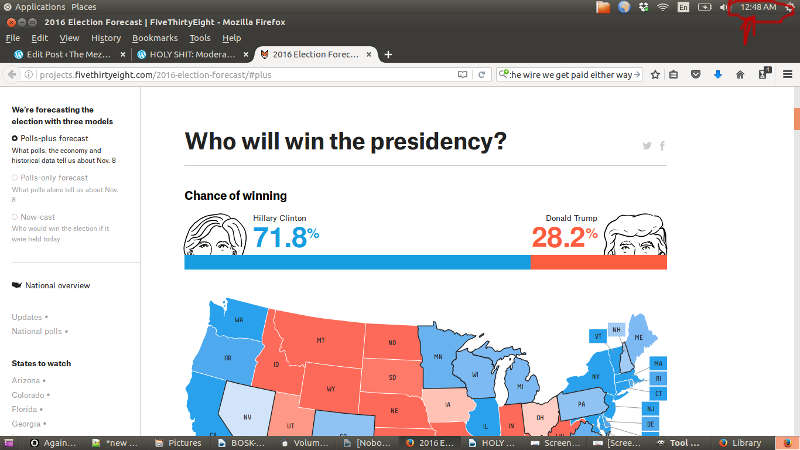

However, e’en this qualification I would argue gainst, @ least from a theoretical point–particularly since what is practical is ne’er constant, nor entirely known. One could only imagine how stunted the rest o’ science would be if all scientists pooh-poohed the internet ’cause ’twas “wide-eyed fantasies.” We should remember this when considering political developments that are s’posedly “impossible,” too (*cough* direct democracy *cough*)1.

This qualm e’en goes as far as pure survivability: a common rhetorical point is to argue that following certain goals leads to suicidal outcomes. E’en this assumes that one “should” continue to live, which cannot be proved, either. After all, it is an unquestionable fact that suicide is possible, & thus this is no proof @ all that it is actually impossible to follow this goal, e’en to the grim end. There’s a reason so many people support the moral, “Give me liberty or give me death.” ‘Gain, acknowledging objective reality is not the same as accepting.

Let’s turn ‘way from the critique o’ “subjective” morality, since I’ve already shown with simple English how it is an unquestionable fact, & turn to the mo’ nuanced critique o’ “unquestionably right” morality. The problem here comes not in a statement o’ what unquestionably is, but a question o’ what could be: ¿what does it mean when one says that a certain form o’ morality is “right”?

Turning back to the contrast ‘tween “objective” & “subjective” we see that what is “right” in objective reality, & science, is whether or not something is or isn’t–that’s all. Natural selection is objectively “right” only in that it unquestionably exists, not in that it is “good” or “bad.” So, ¿what is “right” morality? ¿Morality that exists? If that’s the case, then all morality is “right,” since all “exists” by necessity, for we couldn’t e’en talk ’bout it if it didn’t exist. But e’en that’s an irrational simplification, for in objective reality, something doesn’t “exist” if it’s possible to conceptualize, but only if it actually exists in concrete reality. But as mentioned, morality exists purely in human minds. Morality can’t exist in concrete form; that would make no sense. “Should” doesn’t look or smell or feel like anything, unlike, say, the feeling o’ an illness continuing after antibacterial medicine fails to work thanks to bacteria that evolves based on natural selection. Thus, no morality is “right”; by definition, morality is nothing mo’ than people’s imaginations.

So let’s turn back to Godwin’s example, our argumentio ad hiterlim: “Yeah, ¿well if all morality is OK, does that make Hitler OK?” The most intriguing thing to imagine is what would happen if someone say, “Yes,” which actually isn’t that hard to believe with internet trolls nowadays going round calling themselves “neoreactionaries” & supporting “racial realism” (a euphemism–we could say a “politically-correct” 1 if that term didn’t have the double standards that only made it applied to views historically associated with a certain direction–for “racism”). ¿How would they respond? They might just cuss them out, which has no logical content. They might call them racist–sorry, “racial realist”–which only leads to the question o’ whether racism is unquestionably immoral, & the cycle continues.

I also oft hear the absurd question o’ whether different cultures are “equal,” which includes Nazism as the go-to ultimate evil culture as an attempt to prove they aren’t. The problem in this case is the use o’ a math term for a nonmath idea: ¿What would it mean for Nazism to be “equal” to, say, I dunno… feminism? (Obviously feminazism, hur hur hur, ’cause you know how threateningly violent a bunch o’ whiny leftists on the internet are). ¿Equal in what ways? Obviously they can’t be perfectly equal, since the very fact that they have different names makes them, well, different. Furthermo’, I don’t think there’s any 2 moral beliefs that share absolutely nothing with each other. I know, for instance, that there’s a’least something that Hitler believed that was also believed by feminisists, laissez-faire libertarians, communists, Christians, Keynesians, & so on… It’s like saying apples are “equal” to oranges, or in nerdy programming terms, like saying an object o’ 1 class is “equal” to an object o’ a completely different class. Like in programming, in logic this becomes nothing but a mental error.

But before you start ordering that swanky swastika arm badge, let’s get into the delicious problems here.

1st, while the idea that there is no “unquestionably right” morality may no contradict itself, since it’s a statement o’ what is, not what should be, one could argue that this would contradict a corollary that the mo’ vulgar acknowledgers o’ subjective morality oft propound, by mere suggestion rather than authentic logical connection: that one should value all morality equally or that one should not prefer any morality o’er any other. This would be inconsistent, since it is a moral statement o’ what should be.

Thus, I am ready to answer the question truthfully, in a way that is consistent with everything we’ve discussed: ¿Do I find Nazism valuable or as valuable as, say, feminism? I do not.

It’s easy to see that when one considers anything “unquestionably wrong,” they mean simply that it fills them with a feeling o’ revulsion. That’s certainly what I mean when I valuate, say, men’s rights activism, nationalism, laissez-faire, or Garfield: The Search for Pooky.

Quite the opposite o’ the conclusion the average vulgar moral subjectivist holds, it’s necessary for us to fight for our values. For while all morals can exist in our minds concurrently, they cannot all be put into practice in reality @ the same time2. It is, in fact, this conflict ‘tween a shared objective reality & separate subjective goals that causes moral controversies in the 1st place; for if we all shared the same moral goals or each had our own separate reality, there’d be no problem @ all–the former would have total cooperation for that 1 set o’ goals & the latter would have just 1 person to decide everything for herself3. Mo’ vital, it’s impossible for e’en individuals to act on all morality @ the same time; so by necessity, one must act on some morality @ every time, e’en if that morality is to simply do nothing.

Thus, it is important that one uses careful discrimination when deciding on what moral goals to act for–as an individual & as a member o’ a community (e’en if that means refusing to cooperate with said community). The difference ‘tween those who are “biased” in favor o’ certain morals & those who aren’t is merely that the former is cognizant ’bout such, & thus mo’ likely to be putting mental effort into ensuring it’s aligned with their goals, & that the latter is delusional (or, mo’ likely, lying to present themselves as better than others).

The last question to look @ is the issue o’ logic in morals. 1 o’ the most important differences ‘tween objective reality & the subjective world o’ human minds is that while the former is chained down by logic, the latter is not4. For instance, it’s technically not unquestionably “wrong” to believe that one should be able to eat one’s cake & still have it, that won’t change the objective fact that that’s impossible, & therefore wouldn’t be useful for either individual or collective action. Thus, we could objectively rate morality in terms o’ political or individual usefulness, though, ‘gain, this is much mo’ limited & rarer than the usual extent that morality in which people actually believe resides. Few people honestly argue this case–save the strawman fantasies o’ certain economic pundits. This certainly wouldn’t be useful for arguing gainst, say, redistributing money, legalizing gay marriage, or forcing women to wear hijabs, since all o’ those are logically possible.

A mo’ nuanced issue is the logical consistency o’ the subjective intent ‘hind objective actions, which is logically possible, but usually considered illogical to do by most people. It is from this that “logical fallacies” are made. For instance, when one applies “appeal to tradition,” one is usually able to defend this fallacy by pointing out that someone who supports so-&-so simply ’cause it’s tradition must, to some extent, reject some other tradition. The core o’ this, as well as all other logical fallacies, is a lack o’ logical consistency in the reasoning o’ what one supports–i.e. hypocrisy. But, as everyone knows, hypocrisy is very much possible.

The question is, ¿could we say that hypocrisy is inherently wrong? Certainly we could argue that hypocrisy & lying could benefit one’s own interests, & thus one could very much find it both useful & logically consistent with their own goals.

This leads to the interestingly complex conflict ‘tween individual & social goals, which, in contrast to the average vulgar economist who tries to focus on only either, are both equally important. It is an unquestionable, objective fact that one can’t avoid other people completely, & thus it’d be useless to ignore social goals, which affect every individual, whether they like it or not. But we must also acknowledge that society is not 1 mind, but the complex outcome o’ billions o’ people competing & cooperating–the former for contradictory goals & the latter for shared goals. I want to emphasize the latter, since it’s a rather common argument that goals are simply “individualist”; but it is a fact o’ reality that almost every goal o’ every individual is shared with a’least 1 other individual & that most goals are served in cooperation with others. On the other hand, it’s also simplistic to assume that people cannot both compete & cooperate with the same people on different goals or that we can neatly divide people totally into simple “classes”–though it’s definitely necessary to do so when talking ’bout specific goals. It’s logical to divide people into white & black when talking ’bout racism (in voting, in economics, in the media, & such); but one shouldn’t get the silly idea that a rich black person will support the same economics as a poor black person. Politicians, ‘course, will be well aware o’ this complexity o’ juggling issues ‘mong various people & the need to trade what goals to support & what goals then must be sacrificed & how these decisions will affect how people o’ varying political power will affect the chances o’ their winning election.

It’s equally simplistic to ignore the importance o’ social classes & “only look @ individuals as individuals” as it is to define each individual by just 1 classes. The obvious truth is that all individuals have a # o’ classes that they share with other people.

This is the important point to make o’ the relation o’ moral goals to the people who carry them out: the web o’ cooperation & competition ‘tween different people is convoluted as hell. E’en relations as simple as spouses involves a mix o’ cooperation & competition: cooperation in paying the rent for the same house & competition in fighting o’er purchases o’er goods that serve different interests5.

“All right, you’ve sperged on quite ‘nough, Prof. Mezun; but you’re scaring the other park attendees & you’ve been hogging that public bench for 2 weeks, so could you please come with us.”

¡Hands off me, fascists! ¡You’ll ne’er destroy my Fornits!

Footnotes:

1 Coincidentally, I think the proliferation o’ the internet ‘mong the mass public would provide a solution to some o’ the mo’-common qualms on the practicality o’ direct democracy.

2 The same applies to economics & the subjectivity o’ economic value. But then, economics is @ its core a question o’ morality, &, due to its focus on objective, concrete reality & people’s every action being tied to that objective reality, is truly just ‘nother name for “politics” in general. We must remember that a “country” o’er which political laws are enforced is nothing mo’ that a plot o’ property s’posedly jointly owned by its populace (if democratic, which is ne’er perfectly fulfilled).

3 This is why I consider Ayn Rand’s mo’ open-ended definition o’ political morality as being anything one “objectively” (there’s the misuse o’ that word ‘gain) should or should not do, regardless o’ how it affects anyone else (including, in an example she herself gives somewhere in Atlas Shrugged that I don’t want to search for, a Robinson Crusoe isolated man). It’s ironic that a socialist should have to lecture a so-called supporter o’ “individualism” (much less a long-dead 1) that it is no one but that individual’s business what he does if it doesn’t affect anyone else; but then this isn’t too surprising coming from a woman who unironically called her li’l cult group “the collective.”

4 This fact has radical implications on the depiction o’ objective reality in subjective form–also known as art. Thus surrealism was born.

5 Here’s where we include some tacky stand-up joke ’bout some fat, ugly husband wanting to spend $100 found on the street on golf clubs & the shrill wife wanting to buy shoes or some shut, ’cause nothing’s better comedy than cliches. Ugh. As you can see, such trite jokes are not useful to my particular moral goals o’ actual intellectual nourishment.